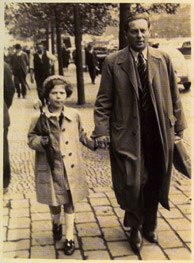

I was born on a cold and damp autumnal day in the northern Bohemia town of Děčín. My parents gave me the name Eva. I started elementary school in Volyně in southern Bohemia. My dad bought a rubber goods factory there and we lived in a large house that was part of the factory grounds. My mum took me to school every day, as she was afraid I might fall into the river water that flowed over a footbridge near the house. My school days were soon cut short though.

I was born on a cold and damp autumnal day in the northern Bohemia town of Děčín. My parents gave me the name Eva. I started elementary school in Volyně in southern Bohemia. My dad bought a rubber goods factory there and we lived in a large house that was part of the factory grounds. My mum took me to school every day, as she was afraid I might fall into the river water that flowed over a footbridge near the house. My school days were soon cut short though.

Jews had to wear a yellow star sewn on their clothes whenever they went onto the street. My friends who used to play with me never came again. Why? Because of that screaming voice on the radio? Or because I was Jewish? The shop where I used to go for ice-cream now carried a sign, saying “Jews and dogs not allowed.” I felt that our life was changing for the worst. My mum and dad stopped smiling.

Jews had to wear a yellow star sewn on their clothes whenever they went onto the street. My friends who used to play with me never came again. Why? Because of that screaming voice on the radio? Or because I was Jewish? The shop where I used to go for ice-cream now carried a sign, saying “Jews and dogs not allowed.” I felt that our life was changing for the worst. My mum and dad stopped smiling.My dad was having success with his laboratory experiments at the time. He managed to produce a special type of bakelite that he had been working on for a long time. Before publicizing his invention, he made various items out of bakelite which he used as samples. He also made a nice powder compact for mum and a snuffbox which he gave to an army friend. Dad was invited to the research institute in Prague, where he showed his new material to expert chemists, and they approved his invention. He was beaming with satisfaction when he returned home. His happiness didn’t last for long, though. Under the new Nazi laws, Jews were not allowed to register inventions under their own names. So my dad handed over the patent copyright to a Czech inventor friend, who was later honoured with a prize that should have gone to my father. We came out of our house the following day. Standing in front of the door, we looked for one last time at everything we were leaving behind – the beds, blankets, pictures, porcelain dishes, games and toys. Who will sleep in my little bed? Who will tuck themselves into the soft quilts? Who will the clown in the picture on the wall smile at? How sad it is to leave one’s home! What has happened? I don’t understand! Why do we have to leave everything and go? We went out onto the street and people stared at us. I was so ashamed. There were about a thousand of us at the Trade Fair Palace. We stayed there about a week, but I can’t remember exactly how long. On the way to the train station, each of us was given a number that stayed with us all the time. My dad’s number was 641, my mum had 642 and mine was 643. From then on we were had no names, just numbers. We got on the train and then set off. There was an oppressive silence in the carriage, everyone immersed in their own thoughts. Looking out of the window, I could see trees covered in snow and small houses in the distance. I envied the trees and the people living in their homes, as we sped by. Several hours later, the train pulled into a small station in Bohušovice, which was about three kilometres from our destination: Terezín. The German soldiers lined us up and led us through deep snow across a field. We trudged along with our luggage, not knowing really where we were going and feeling dejected. I remember that my dad tried to help me by propping me up. Like a lot of other children, however, I sensed that our parents were powerless. We children had suddenly become adults. We knew that nobody could help us and that we would have to look after ourselves, so as to make it easier for our parents. We then arrived at our destination: TEREZÍN. Terezín was surrounded by walls with high and wide earthworks. Founded in 1781, the town was a place where troops were stationed. The civilian population lived in the ordinary houses and earned a living by providing services for the army. Terezín was now turned into a ghetto for Jews from Bohemia, Moravia and other European countries. The Germans ordered the original inhabitants to leave the town. By the time we arrived, Jews from Prague and the surrounding areas were the only ones there, having come on earlier transports. Our family was taken to the barracks. A horrible thing then happened – the German soldiers separated the men from the women and children. All of a sudden, dad was not with us. They took him away from me and my mum. It felt… a bit like dying. It was all very strange and alien in Terezín. A lot of women and children lived together there. The only possessions we had were a straw mattress and a suitcase. Food was given out three times a day. We had to stand in line with plate in hand and to make our way to a serving hatch where we each received our ration: muddy coffee with a slice of bread in the morning, thin soup and a potato in a disgusting sauce that made me sick at midday, and some liquid in the evening. It was a sad time. One day, however, my dad turned up to see us. The Germans had given the men permission to visit their families. It was only then that we found out that dad was living in the other barracks. Some time later the Germans allowed us to leave our barracks, so we could be with dad. We then lived together in a small attic room. We had several cases for furniture and even found some beds and a small stove. Mum managed to cook frugal meals on the stove and it even kept us warm in the winter months. When I think of all the suffering that was to come later on, they were three happy years that we spent in that little room. In time, we all – children and adults alike – became accustomed to life in the ghetto. Every day we went to work wherever our captors sent us. We children, like all others in the world, wanted to play after work, but our games were completely different. We had to work most of the time in compliance with the Nazi orders. We dug up the dry, dusty soil alongside the city walls, turned it into fertile land and then planted various kinds of vegetables. The fruits of our labours were consumed by our captors. Children met each morning at a specified place, where we were then split into groups and marched in rows to the crossbars of the ghetto gates while singing. Young and older children worked together. Those who had studied before the war taught us whatever they could remember from their schooldays. So we learned about a lot of the things that children are usually taught in school. One of the artists organized a large group of children – myself included – and taught us how to play-act. After our work was over, we practiced, rehearsed and sang. One of the plays we prepared was the children’s opera Brundibar. This was written by Adolf Hoffmeister and put to music by Hans Krása before the war. It was premiered in front of a Terezín audience. The Nazis knew how to deceive not only us, but the rest of the world. One day we found out that our ghetto was to be visited by representatives of the International Red Cross. In order to outwit their guests, the Germans set about transforming Terezín beyond recognition. The facades of houses around the high street were newly rendered and repainted, while the streets were swept and cleaned. Groups of children dressed in their best clothes stood around on a street corner, nibbling away at sardine sandwiches. They had been ordered to wait until the members of the international commission appeared in the company of the camp commander, who was called Rahm. One of the children then had to go up to him and say in German: “Uncle Rahm, not sardines again?” This was all staged, of course. The Germans intended to show that we had sardines so often that we no longer wanted them. To this day, whenever I serve the same food twice in a row, my family jokingly protest: “Not sardines again?” The International Red Cross envoys were really fooled, as a result of which a false impression of the ghetto spread across the world. In their report, they wrote that the claims regarding Nazi brutality were not legitimate; the ghetto conditions were acceptable and comfortable, everything was in order and there was no reason for concern. At that time we often spoke about God and whether he existed and saw all that was happening to us. We asked why he remained silent and did nothing to help us. We thought that God was testing us, while others claimed that he would help us when things came to the worst. I had a small diary and in the evenings would write down everything that had happened during the day. I imagined being in Prague, sitting on my bed, eating a large slice of bread smothered in jam that my mum had made. I can now read in this diary everything that I went through in Terezín. Years of work, hopes and suffering slipped away, summer and winter passed. Each summer we consoled each other that the war would be over in the winter. When that didn’t happen, we were convinced that it would be over next summer and that we would finally be able to go home.  Several weeks later, the Germans ‘allowed’ us to join the men. Along with many others, my mum and I rushed to register for a place on the transport. We thought that we would be meeting up with dad. We got on the train on the appointed day. It wasn’t a cattle truck, like the other transports, but a regular passenger train. We occupied a seat by the window above which hung an ad for Pilsner Beer. Taking a closer peak at the picture, I lifted it slightly and saw what was written underneath in German: WE ARE GOING TO AUSCHWITZ! Although we didn’t exactly know what this meant, my mum asked me not to tell anyone about it.

Several weeks later, the Germans ‘allowed’ us to join the men. Along with many others, my mum and I rushed to register for a place on the transport. We thought that we would be meeting up with dad. We got on the train on the appointed day. It wasn’t a cattle truck, like the other transports, but a regular passenger train. We occupied a seat by the window above which hung an ad for Pilsner Beer. Taking a closer peak at the picture, I lifted it slightly and saw what was written underneath in German: WE ARE GOING TO AUSCHWITZ! Although we didn’t exactly know what this meant, my mum asked me not to tell anyone about it.The train journey lasted three long days. At night the train stood on the tracks for hours on end. Looking out of the window, we gazed at the stars in the black sky. Mum taught me their names and showed me the Big Dipper constellation. Those were the last peaceful moments we had before arriving at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in Poland. As soon as the train came to a halt, the carriage doors opened to the sound of terrible shouting, cursing and dogs barking, which almost deafened us. The soldiers yelled in German: “Get out! Quick, quick! Leave everything behind!” They drove us off the train, beating us with sticks. The small suitcase with my diary and a chocolate bar that I had saved for dad – a present from a kind Czech gendarme who sometimes helped us out in Terezín – was left on the train. There was unimaginable chaos. The soldiers moved us forward with violence, kicking us. I felt as though a pack of madmen had swooped on us. I was terribly afraid. They put us in rows and I clung to my mum’s hand out of fear. One of mum’s friends who had left Terezín earlier suddenly appeared before us. Without saying a word, she grabbed me and pushed me in the row behind my mum. She held a finger to her lips to indicate I must be quiet, and quickly whispered in my ear that I was to pretend to be 18 years old. Later on, my mum explained to me that younger children were separated from their mothers and never seen again. My mum’s friend saved my live. We were forced to undress, had our heads shaved and were given ragged prison clothes. We were then led through the mud to some large buildings in the women’s camp C. Tall, belching chimneys towered above in the background. The women prisoners in the camp just shrugged their shoulders when asked what the chimneys were for. We asked about the men’s transport from Terezín, but they just waved their hands towards the chimneys. We soon discovered that the chimneys were part of a crematorium where my dad was taken on his last journey. We then understood the blatant lie about the ‘new camp’. After six weeks of terrible suffering, they drove us out in front of the buildings one day. Doctor Mengele, the brutal Auschwitz doctor, had come to select a group of healthy young women for work details. Watching the naked women as they walked in front of him, he decided with a wave of the hand who was to go to the right and live and who was to go to the left and be sent to the gas chamber. After the selection, we found out that we would be sent out of Auschwitz to work in another camp. Once again, we felt a glimmer of hope. Before leaving the camp, we were given clothes and shoes. By mistake I ended up with two left shoes. Sheepishly, I went up to the pile of shoes to swap a shoe. I suddenly felt a blow from a rifle butt. A German guard beside the pile hit me in the face, knocking out my two front teeth. So I was stuck with the two left shoes. With strong will, however, I found that you could get by with two left shoes. The camp we were taken to was situated in the middle of a snow-covered forest. This was to be our new workplace. All the prison inmates were digging trenches and putting up barbed wire. It was terrible work, particularly in the midst of a harsh winter. One day a miracle occurred: during morning roll call, I was noticed by the camp ‘komandant’. Seeing that I was barefoot in the snow, he pointed to a wooden building at some distance from the camp and told me to go there. To my great surprise I found a girl there who was about three years older than me. She was called Goldi and spoke only Hungarian. I was given to understand that this was the komandant’s dwelling or workplace and that I had to clean up. In the middle of the room was a small cylindrical stove, which gave off wonderful heat. It was like being in a dream: standing in the middle of a warm room. Goldi and I cleaned the place every day, while trying to warm our emaciated bodies. One day the komandant brought me some shoes, in which I was later to walk about 600 km on the death march. Trucks full of armed German soldiers drove into the camp one evening. They had large Alsatians on a chain. We were scared stiff, as we didn’t know what this all meant. Before sunrise they forced us out onto the death march. Each day we had to walk between 30 and 40 kilometres. We slept by the roadside, even in the freezing frost, and fed on the weeds that peeped up through the snow, tree bark and any refuse that happened to be lying around. Throughout that time we suffered terrible thirst, which we quenched with melted snow. A cup of thin soup and a small slice of bread was all we got to eat in the evening. We passed by populated areas on the way. We envied the people who lived in their warm houses and were not starving. I regretted that it was not in our power to escape, but the Germans guarded us as if we were some kind of rare treasure. The women who tried to run away were soon caught by the dogs and shot on the spot. My mum got terribly weak on the death march. She closed her eyes and softly whispered to me: “Eva, I can’t go on.” She kissed me and her eyes said it all. I felt it, but could not mentally come to terms with it. I kept talking to her, as if I didn’t know I had just lost my mum. When they were handing out bread, they threw my mum a slice, not realizing that she was no longer alive. I ate both slices. After another whole day’s hard trekking, we took shelter in a barn for the night. The hay on the floor reeked, but at least it gave off a bit of warmth. I tucked into a small heap of hay and fell into a deep sleep. In the morning I was awoken by someone speaking Polish. When I opened my eyes and looked around, I realized that everyone else had left and I had remained alone. I waited until it got dark and then took off. There was a full moon and the sky was full of stars. For a while I was absorbed by the silence of the night and by a feeling of freedom in the wide open fields. I set off on my journey without knowing where I was going. I walked all night and by daybreak found myself in a flower-strewn meadow. I realized that spring must have come. I picked a small flower, which gave me pleasure, and continued on my journey until I reached a railway track, beside which I lay down and fell asleep, exhausted. I woke up with a start. Above me stood a German soldier. I told him the truth in answer to his questions and he admitted that he was on the run too. I suddenly lost all fear. The soldier sat next to me, took out a piece of bread and a coffee jar from his rucksack. We are together. I found out that it was April 1945 and that the Germans were at the end of their tether. The war would soon be over. The soldier had escaped from the front and needed to get rid of his uniform. In the end we wished each other all the best and went our separate ways. The following day I met three young Czech boys. Gazing at me with a mixture of horror and surprise, one of them said: “Hey, there’s a ghost coming our way.” I probably looked like one to them. They started asking me questions, so I told them some of the things that had happened, but they just shrugged their shoulders as they thought I was making it all up. Anyway, they said we were at the Czech border and that I could go along with them. I couldn’t keep up to them, however, and they disappeared in a field. So I was alone once again. In the morning I set off on the quickest route which the three Czechs had taken ahead of me. A short while later I reached a stream that was about three or four metres wide. On the other side was a village. But how could I cross a stream with water from melting snow pouring down? Using a long, sturdy branch that I found, I managed to reach a low ford after several attempts. I then went up to the first large house and knocked on the door. Not waiting for a reply, I carefully opened it and looked inside. I glimpsed a row of polished army boots that had been neatly placed in the hallway. Without even closing the door, I fled as fast as I could, away into the field. I then fell on the ground.  One morning I heard an excited voice saying “Eva! Eva! The Germans have gone, the war’s over!” I came out of my hiding place. Around me everyone was embracing each other and dancing. An American tank festooned with flags drove into the village and the soldiers in it were throwing chocolate bars to the children. The village band played and the drummer lifted me up onto his shoulders. The procession went through the village. I wasn’t able to really rejoice, though. Back home, I then burst into tears for the first time during the entire war. I cried for all those who had not lived to see the end of the war, for dad and mum, and because I was the only one left. I didn’t have the feeling I had won.

One morning I heard an excited voice saying “Eva! Eva! The Germans have gone, the war’s over!” I came out of my hiding place. Around me everyone was embracing each other and dancing. An American tank festooned with flags drove into the village and the soldiers in it were throwing chocolate bars to the children. The village band played and the drummer lifted me up onto his shoulders. The procession went through the village. I wasn’t able to really rejoice, though. Back home, I then burst into tears for the first time during the entire war. I cried for all those who had not lived to see the end of the war, for dad and mum, and because I was the only one left. I didn’t have the feeling I had won.I felt that I couldn’t conceal my identity for long. They understood everything, as always, and uncle Jahn just said: “How could you have thought we would leave you to your fate?” They weren’t angry at me and I was very grateful to them for this. Uncle Jahn put my name on the survivors list at the Jewish community in Prague. There was still a small chance that my dad was still alive and that he was looking for me. One day, at noon, a woman I didn’t know turned up at our place. She said she was my aunt. She had found me on the list and come for me. I didn’t feel too good around aunt Ilona from the outset and I didn’t want to go with her. Uncle Jahn saw things differently though. He explained that it would be good for me and that I could come back whenever I want and the family would welcome me with open arms. In the end, he persuaded me to go. We said our goodbyes at the train station. I was unable to speak, as I was choked with tears and felt heavy-hearted. I had bad associations with train stations. I didn’t know what was in store for me at the next station. My life with aunt Ilona was not easy. I enquired at the nearest Jewish community about my prospects of getting help. I found out that I could apply to stay at the Jewish orphanage in Prague, where there were children like myself. I began impatiently to count down the days… My big day finally arrived. I packed my stuff in a small bag, carefully tucking in my greatest treasure – a family photo album that had been salvaged – and set off to the nearby train station. In my pocket I had 200 crowns that the Jewish community had given me for my welfare. I bought a ticket at the station counter and, with a mixed feeling of freedom and fear, I got on the train and sat by the window. The train set off. I arrived in Prague at ten in the evening. The station was swarming with people. I went out onto the streets, where there were also endless streams of people. Where were they all heading? Trams rang their bells and were going here and there. I tried to spot a policeman to get directions. A few minutes later I luckily came across one. He showed me how to get to the address that was written on a card: Belgická 25, Prague 2. He advised me to get on tram 20 at the next stop. I looked out of the window at familiar places and gradually started to recognize them – here was the museum that I visited several times with my dad, there was the square with the statue of the horse and the noble horseman in armour and with sword in hand. I was overcome with a flood of memories. Five years earlier, I had been at all these places as a happy and contented child with my mum and dad. And now – they were no longer alive, but nothing had changed here: the same old streets, houses and people.  Engrossed in my thoughts, I didn’t notice the tram stops that we passed. Fortunately I got off at the right stop and reached my address. I found myself in front of a large brown building. It was late and the front door was locked. I rung the bell and, after a short while, the door was opened by a sleepy woman porter. She let me in without asking any questions. I went upstairs and entered a large room with a sofa and table in the corner and lots of chairs around the place. On the wall there was an oil painting of a landscape, and I was amazed because it was a picture from our old apartment. My parents were given it many years ago. How did it get here? I had a jabbing sensation in my heart and felt the warmth of my lost home from this picture...

Engrossed in my thoughts, I didn’t notice the tram stops that we passed. Fortunately I got off at the right stop and reached my address. I found myself in front of a large brown building. It was late and the front door was locked. I rung the bell and, after a short while, the door was opened by a sleepy woman porter. She let me in without asking any questions. I went upstairs and entered a large room with a sofa and table in the corner and lots of chairs around the place. On the wall there was an oil painting of a landscape, and I was amazed because it was a picture from our old apartment. My parents were given it many years ago. How did it get here? I had a jabbing sensation in my heart and felt the warmth of my lost home from this picture...

The story of Eva Löwidt-Erben is captured in more detail in a 45 minute documentary film by Pavel Štingl About a Bad Dream, on the DVD 2x Book of Destiny.. |