|

|

Before the war

Before the war

I was born in January 1932 into the family of a commercial traveller who worked for the Kudrnáč Náchod company. My sister Lenka was born in 1935. We were neither rich nor poor. We had a nice well-appointed flat in a tenement house in Pardubice. My father came from Poland and thus he was more religious, while for my mother, who was a real Czech Jew, religion did not play any part in her family. We only celebrated the main holidays. I attended religious education classes (doesn’t rhyme like lessons) given by the rabbi in Pardubice; I think his name was Feder. I had gone to a synagogue with my father several times but it did not interest me at all and the only one thing I remember was blowing the shofar.

I was born in January 1932 into the family of a commercial traveller who worked for the Kudrnáč Náchod company. My sister Lenka was born in 1935. We were neither rich nor poor. We had a nice well-appointed flat in a tenement house in Pardubice. My father came from Poland and thus he was more religious, while for my mother, who was a real Czech Jew, religion did not play any part in her family. We only celebrated the main holidays. I attended religious education classes (doesn’t rhyme like lessons) given by the rabbi in Pardubice; I think his name was Feder. I had gone to a synagogue with my father several times but it did not interest me at all and the only one thing I remember was blowing the shofar.

I attended the first and second grades of basic school in Pardubice and I was an obedient pupil. I was never detained and also never got acquainted with the ruler of our class teacher.

Germans are coming

I remember the arrival of the German army very well. The main road was not far from our place and motorcades of army vehicles with Germans rolled down it. I did not feel threatened by the arrival of the Germans at that moment nor could I feel any tension in our family. My parents did not pass the situation on to us children at that time but later, I cannot determine it more precisely in time, I began to perceive it. It must have been at the end of the second grade, I could read then. (I was attending private German lessons given by evil teacher Mrs. Hochová with one friend of mine. She had a big dog, a Doberman that I was afraid of and of her as well). I discovered in Pardubice – at that time there was still no ban on entering some streets in the town – anti-Semitic drawings in the shop-window not far from the small park where the statue of president Masaryk and the slogan “The truth wins” below it used to stand. It was an old shop that was later confiscated by the followers of a political movement Vlajka (Flag), who were Czech fascists. There were ugly faces with crooked big noses and some repulsive words. I do not know exactly what was written there but it must have been something very ugly if I remember it.

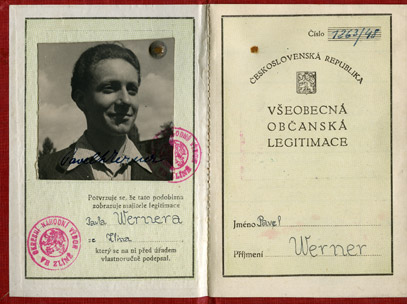

I also understood that the Germans represented danger. When I saw the boys from the Hitlerjugend in the streets I immediately hid – and I didn’t even wear the badge – a Jewish star sewn on the clothes and neither I nor anyone in my family looked like a “typical” Jew. You can see from the photographs of those times. Therefore I – an eight-year old boy – must have known those boys posed a danger to me. And then something horrific happened. The financial situation of my parents was probably bad (The Kudrnáč company dismissed my father and he was unemployed) when an advertisement offering rent for one room appeared on the ground floor (we lived on the first floor). The single room was a dining room which was not used very often, only sometimes on some holidays – sender etc.

What happened was that some German moved in. He was wearing a badge with a swastika (it was a NSDAP badge) on his lapel, and had a military car come for him. I remember the conversation my father had with him when he came and when my father told him about our position. The German told him he did not care. So he continued to live downstairs. Surprisingly he was a respectable man. Nothing happened at our place; he behaved respectfully and used no abusive language. But one could feel the tension in the family.

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

And then the situation began to change completely. I managed to finish the second grade of elementary school. I do not know why but I was not attending the school where I finished the first grade. I had to go far away beyond the square. Why, I do not know. After finishing the school term – probably in 1940 – we moved from our flat to the periphery of Pardubice. I had to wear a badge and could not attend a normal school. I went secretly to learn with my compatriots. Class was in the rabbi’s flat just next to the synagogue and the way there was very complicated. (In fact it was not just any school; there were children of different ages and our teacher was a young girl, probably a former student at secondary school.) I could not follow the shortest route there as entry to many streets was prohibited to Jews. It was very far away as the synagogue was in the centre of the town and we lived far out, near the temporary housing jerry-built colony called Hawaii on Prague Street. We had two rooms – a kitchen and a room without a toilet or bathroom.

And then the situation began to change completely. I managed to finish the second grade of elementary school. I do not know why but I was not attending the school where I finished the first grade. I had to go far away beyond the square. Why, I do not know. After finishing the school term – probably in 1940 – we moved from our flat to the periphery of Pardubice. I had to wear a badge and could not attend a normal school. I went secretly to learn with my compatriots. Class was in the rabbi’s flat just next to the synagogue and the way there was very complicated. (In fact it was not just any school; there were children of different ages and our teacher was a young girl, probably a former student at secondary school.) I could not follow the shortest route there as entry to many streets was prohibited to Jews. It was very far away as the synagogue was in the centre of the town and we lived far out, near the temporary housing jerry-built colony called Hawaii on Prague Street. We had two rooms – a kitchen and a room without a toilet or bathroom.

But I liked it there. There was a small garden where we were breeding rabbits and we had also a tom-cat although it was prohibited, as the Jews were not allowed to keep any animals.

The house belonged to an older couple who did not have children and who were producing files and rasps. There was a small workshop where the owner, Mr. Lochman, worked with one employee of his. His name was Mr. Kunc. I often observed in the workshop how the files were being processed.

But I liked it there. There was a small garden where we were breeding rabbits and we had also a tom-cat although it was prohibited, as the Jews were not allowed to keep any animals.

The house belonged to an older couple who did not have children and who were producing files and rasps. There was a small workshop where the owner, Mr. Lochman, worked with one employee of his. His name was Mr. Kunc. I often observed in the workshop how the files were being processed.

Terezín

Suddenly biscuits started to be baked at our place. They were thick and my parents wrapped them in greaseproof paper. I did not know why but soon I understood. It was Autumn 1942 and we, together with the others from Pardubice, left with the transport Cg for Terezín. The gathering place) was in the commercial academy which is close to the station. The way from Pražská street was long and Mr Lochman lent us a small four-wheel handcart that was used in those times. He followed us and kept a respectful distance. When we were close to the destination we left the handcart behind and carried our things by hand. Then he took the handcart back. That much I was able to observe.

The journey by train was normal, we were in passenger’s cars. It was worse at the destination. In those times there were no tracks leading to Terezín and it was necessary to get off in Bohušovice. Though it was only 3 – 4 kilometres to Terezín, it was in fact the first time I suffered. I had winter clothes on though it was not winter yet, I dragged a heavy rucksack and was crying that I could not go on any more. My father told me off and pointed at my sister Lenka who walked patiently.

My evaluation of the stay in Terezín is in my mind influenced by the stay in other camps – Auschwitz- Birkenau, Mauthausen, Melk and Gunskirchen. It was possible to endure in Terezín if one was not old or if he did not fall ill with some serious disease. That was fatal for my little sister Lenka who fell ill with meningitis and died. Later I told myself that by all means it was a “better death” than dying in a gas chamber.

First I lived with my mother and sister and other women, then I was moved to boys’ home L417. I helped my mother keep the tidyness of the toilettes (the so-called Klowache) – my duty was to check after everyone if everything was clean and I liked doing that as I was important and I could be cheeky to elders. I wandered a lot through the Hannover barracks (my father lived there) – better said in the washroom there because I was looking for the wrappers of razor blades for my collection. I also helped secretly (so that my mum did not know) one man who separated paper from the rubbish and then pressed the paper in a small room so it could be reused. Again there I looked for the wrappers of razor blades. I found there a small textbook of Russian and I learned the Cyrillic alphabet! In Terezín in 1943. I do not know how I got there but several times I appeared as a solo singer of the song Volga, Volga (about Stenka Razin) in the group of Freizeitgestaltung.

My father worked in a joiner’s workshop. And after work he made shelves from „spared“ material – we got something to eat for that. The best tidbit was a bread cake - normally it would not taste good to anybody but there it was an outstanding delicacy.

Transport to the East

And then in May 1944 my parents and I were sent in the transport Dy-1188 on the 15th May 1944 to Auschwitz. And this time it was a dreadful though not so long journey. There were a lot of us in a cattle wagon and only one bucket of water and one as a lavatory for all.

Auschwitz and the family camp

We arrived at Birkenau at night and I remember that night very well. It was filled with a lot of lights and terrible shouting from those who were unloading us from the wagons. Just during the road to the family camp BIIb some prisoner from the commando accompanying us wanted to exchange shoes with my father saying that they would take them from him anyway. He was Polish. My father did not exchange them.

The accommodations at the block (that is how the barracks were called in the camp) had no windows and 600 prisoners sleeping on 4 decks – I was with my father and it was terrible compared to Terezín. Some kapo (warden made from a prisoner) was running the block, he was Polish and was shouting at us that we were not in Terezín any more and that we would finish in a chimney. I did not understand the chimney but later I knew what was going on. I do not why but my father was hit by a blow from a stick of the so-called Lagerkapo (who was in the highest rank after the prison boss of the entire camp BIIb.) Every kapo had a stick and was allowed to kill a prisoner although he was a prisoner as well. In that time the former executioner from Terezín named Fischer was the lagerkapo. He was a semi-hunchbacked ugly-looking man. He was running alongside the camp and beating anybody without reason with a stick. Surprisingly I met him again when the Auschwitz camp was being liquidated in January 1945 while we were marching to the train. He joined us boys and was very friendly but I was very scared of him. Then he got lost while we were marching in frost for three days, one night without any rest. Probably he could not stand the pace and at the end of the ranks consisting of about 1.000 men he was shot dead. That was the end of all those who could not carry on. I was with the boys kept in the middle of the rank because to be at the front meant to clean up the corpses of those who remained from the preceding group – everyone had his skull shattered – the Germans shot from point-blank range with rifles leaving a totally smashed head and brain scattered all around. We also did not want to be at the back, if one of us could not go on, we would have helped him and not left him at the mercy of the Germans. That whole night we marched always in a group of three boys; each on one side holding an arm and the boy in the middle marching with his eyes closed and having a rest, we all took turns being in the middle.

The accommodations at the block (that is how the barracks were called in the camp) had no windows and 600 prisoners sleeping on 4 decks – I was with my father and it was terrible compared to Terezín. Some kapo (warden made from a prisoner) was running the block, he was Polish and was shouting at us that we were not in Terezín any more and that we would finish in a chimney. I did not understand the chimney but later I knew what was going on. I do not why but my father was hit by a blow from a stick of the so-called Lagerkapo (who was in the highest rank after the prison boss of the entire camp BIIb.) Every kapo had a stick and was allowed to kill a prisoner although he was a prisoner as well. In that time the former executioner from Terezín named Fischer was the lagerkapo. He was a semi-hunchbacked ugly-looking man. He was running alongside the camp and beating anybody without reason with a stick. Surprisingly I met him again when the Auschwitz camp was being liquidated in January 1945 while we were marching to the train. He joined us boys and was very friendly but I was very scared of him. Then he got lost while we were marching in frost for three days, one night without any rest. Probably he could not stand the pace and at the end of the ranks consisting of about 1.000 men he was shot dead. That was the end of all those who could not carry on. I was with the boys kept in the middle of the rank because to be at the front meant to clean up the corpses of those who remained from the preceding group – everyone had his skull shattered – the Germans shot from point-blank range with rifles leaving a totally smashed head and brain scattered all around. We also did not want to be at the back, if one of us could not go on, we would have helped him and not left him at the mercy of the Germans. That whole night we marched always in a group of three boys; each on one side holding an arm and the boy in the middle marching with his eyes closed and having a rest, we all took turns being in the middle.

I did not stay very long in the so-called family camp. In July there was a liquidation of the camp. First came the selection of all the prisoners. We stood in a row, naked in front of Dr. Mengele, who was a head doctor in Auschwitz. He also carried out experiments on twins. I and my father went in the row together, he went behind me. Mengele sent me to one side and had my tattooed number taken down, my father was sent to the other side – which meant a gas chamber and death. Shortly after the selection they transferred me with about 90 boys aged 14 to 17 to a men’s camp. There were only about three of us boys who were not 14 yet. I was only thirteen in 1945. From the rest of about 4.000 to 5.000 prisoners from Terezín, several hundred were selected for work in Germany (in fact they were sent to other concentration camps in Germany) and the others – men, women and children were sent to gas chambers and cremated in crematoria within three days. We saw the smoke, the men’s camp as well as the former family camp were not far from the gas chambers and crematoria. We could see the flames issuing from the chimneys and smell the smoke of burned human bodies.

In the men’s camp (the so-called camp D) I worked as one of thirteen boys hitched to country wagons. These were wagons with wooden wheels provided with iron tires. Normally the wagons were pulled with horses, now we replaced them. We carried anything, loading and unloading. We also went to partly demolished gas chambers (at the end of 1944 they stopped killing by gas) and carried away various things. My wagon, the so-called Rollwagen, fortunately had an understanding kapo. Though he was German with a green triangle (criminal) he treated us humanely. He did not beat us although he also had a stick - that was the normal equipment for the kapos. The worst thing was that like the others I suffered from terrible hunger. And the hunger was so obstinate that one could not think of anything else but food – not any delicacies but of an ordinary massive slice of bread and hot tea with it (in the winter). At night I did not dream about home but bread. Another torment for me was the fear that they would send me to a gas chamber at some selection. I went through these selections twice more and I remember I burst in tears that I would not pass.

In the men’s camp (the so-called camp D) I worked as one of thirteen boys hitched to country wagons. These were wagons with wooden wheels provided with iron tires. Normally the wagons were pulled with horses, now we replaced them. We carried anything, loading and unloading. We also went to partly demolished gas chambers (at the end of 1944 they stopped killing by gas) and carried away various things. My wagon, the so-called Rollwagen, fortunately had an understanding kapo. Though he was German with a green triangle (criminal) he treated us humanely. He did not beat us although he also had a stick - that was the normal equipment for the kapos. The worst thing was that like the others I suffered from terrible hunger. And the hunger was so obstinate that one could not think of anything else but food – not any delicacies but of an ordinary massive slice of bread and hot tea with it (in the winter). At night I did not dream about home but bread. Another torment for me was the fear that they would send me to a gas chamber at some selection. I went through these selections twice more and I remember I burst in tears that I would not pass.

Daily regime: In the morning there was a roll call for “breakfast” which consisted of a canteen of lukewarm coffee substitute. Then Rollwagen, in the afternoon, we returned to the camp and had lunch = a canteen of turnip soup. Then free time, dinner = a small slice of bread (about half of a slice of dark bread resembling bread sold today under the name “Moscow bread”). On the slice we would have one half of a slice of salami or a spoonful of marmalade or a small piece of margarine – this order repeated regularly but never more than one ingredient at a time. As there were neither clocks nor calendars or anything like that it was impossible to tell what time of day it was. The roll call, so-called apel, was in the evening – we waited for the Blockführer who checked to make sure nobody was absent. Sometimes we stood for several hours. We also sometimes had to march and sing.

In the D camp I lived together with the others in block 13, it was the so-called Strafblock. It was separated by a wall from the other blocks at the camp. There were the prisoners there who somehow broke the camp rules and then several hundred Soviet war prisoners of higher categories. Not ordinary soldiers. They were amazing people. They had extra hard labour, often they tried to escape – always were caught and beaten bloody and finally hanged. Almost every evening they sang the Russian gloomy songs, I liked them very much, they were heroes for me. I grew fond of one who took after my daddy a little. I could not talk to him but I followed him like a little dog.

Death March

In January 1945 we could hear the gunfire, Auschwitz was being liquidated. They wanted to leave us children, in the camp but we were afraid to stay there and pushed into the march. If we had stayed there the Soviets would have liberated Auschwitz 10 days later and we would have been saved from an even more dreadful torment: a three-day death march to the train, the journey on open crowded wagons to Mauthausen, from there a march to Melk and back to Mauthausen again – that was in March 1945. The camp was so overcrowded that the prisoners (and a small number of us boys) slept under a circus tent. And then in April, there was the last death march to Gunskirchen close to Wels. There it was the worst of all. The camp in the forest was overcrowded, we could sit on the ground in the barracks with stretched legs one in another, it was raining outside and cold – in one word horror. We drank water from puddles, us children could not get food – the prisoners were fighting for it and we did not have enough strength to join the fight. Maybe a week or ten days and it would have been the end of me and the other boys. Fortunately the Americans liberated the camp on 4th May and I survived.

I returned home

At the end of June I returned to my home country. I remained absolutely alone without any relative. For one year I stayed with the Červinka family, they were very kind people who knew my parents and I enrolled at the 4th level of lower secondary school according to my age. I had a lot to catch up with because of the delay at school but I managed. Our class teacher grew fond of me and he took me under his wing. A professor at the commerce academy, Alfréd Eisner, became my guardian. It was he who sent me to Zlín to take an apprenticeship course to be a shoe maker but first he sent me to the Jewish orphan home at Belgická 25 where I went through a one-year training course compulsory for all students of the lower secondary school. He looked after my matters and I am very grateful to him for all his help.

At the end of June I returned to my home country. I remained absolutely alone without any relative. For one year I stayed with the Červinka family, they were very kind people who knew my parents and I enrolled at the 4th level of lower secondary school according to my age. I had a lot to catch up with because of the delay at school but I managed. Our class teacher grew fond of me and he took me under his wing. A professor at the commerce academy, Alfréd Eisner, became my guardian. It was he who sent me to Zlín to take an apprenticeship course to be a shoe maker but first he sent me to the Jewish orphan home at Belgická 25 where I went through a one-year training course compulsory for all students of the lower secondary school. He looked after my matters and I am very grateful to him for all his help.

I completed the apprenticeship course for a shoe maker in Svit Zlín (formerly and now again Baťa), later I graduated from the University of Economics, specializing in foreign trade. I worked in Motokov and Merkuria, both foreign trade companies, and took a long-term stay in Mexico and Bolivia where I sold our cars. When I returned from Bolivia I travelled almost throughout the entire world with Merkuria and I learned several world languages.

Now I have been retired for a long time and am a vice-chairman of the Terezín Initiative which is the organization for former Jewish prisoners of concentration camps. I have one daughter and three grandchildren. Sometimes I meet with young people and tell them what I as a Jewish child had to undergo during the Second World War.

Now I have been retired for a long time and am a vice-chairman of the Terezín Initiative which is the organization for former Jewish prisoners of concentration camps. I have one daughter and three grandchildren. Sometimes I meet with young people and tell them what I as a Jewish child had to undergo during the Second World War.

|

|

|